The Covid-19 pandemic has unfortunately undermined non-virtual visits to cultural monuments, art galleries and museums in recent years. Back in Europe for some time, I felt the need to reconnect with some of its strong cultural legacies. As I just visited a few masterpieces of Catalan modernist architecture in Barcelona, I don’t resist sharing hereafter my personal interpretation of this awesome cultural journey.

Catalan modernism is an art movement that was born in the late 19th century in a context of revival of regional culture and major urban and industrial development in Catalonia, particularly in Barcelona. It crystallised mainly in the realm of architecture which borrowed substantially from literature, painting, sculpture and the decorative arts in order to reinterpret and blend them into a distinctive artistic style. The Catalan modernist architecture is best illustrated by the work of Antoni Gaudi and Luis Domenech i Montaner.

Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia

Antoni Gaudi’s passions in life were architecture, nature, and religion. Ardent catholic believer, he devoted most of his late professional carrier to the conceive and build the Sagrada Familia. At the time of his death in 1926, less than a quarter of the gigantic project was completed. It is still a major piece of architectural work in progress to date.

When handing his degree to Gaudi in 1878, the director of Barcelona Architecture School reportedly commented as follow: “We have given this academic title either to a fool or a genius.” There is no more doubt nowadays about Gaudi being a genius.

Influenced by new-Gothic and Oriental techniques, Gaudí integrated the Catalan Modernist movement which blossomed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He developed a personal style beyond mainstream modernism, inspired by the Nature and Catalan traditional handicraft, but also relying abundantly on geometric shapes and technical innovations of his invention.

Unlike his fellow architect Montaner, Gaudí did not embark into Catalan politics, considering his architectural work as enough to serve the Catalan cause. He devoted his life to his profession, remaining single. First rather an urban dandy, he largely neglected himself during his last years. Gaudy died tragically in 1926, run over by a tram in Barcelona. Unconscious and assumed to be a beggar, he receive only very basic first health care. He was identified only one day later, shortly before his passing-away. Gaudi’s remains are buried in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia.

The main body of the church is conceived in an organic style to resemble natural shapes. Constructed between 1894 and 1930, the Nativity façade was the first façade to be completed. Dedicated to the birth of Jesus, it is decorated with elements typical of Gaudí’s naturalistic style.

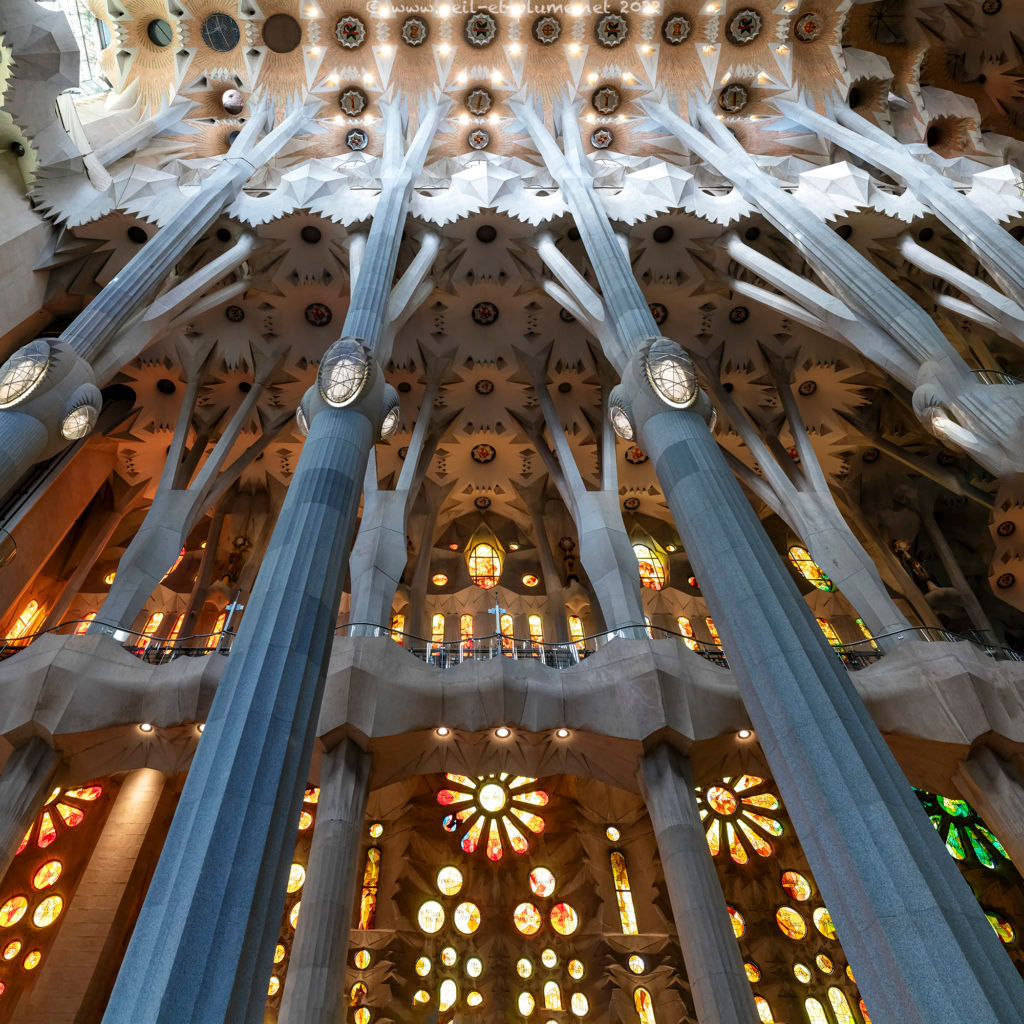

The interior is like a forest, with inclined columns as branching trees. Gaudí applied all his previous experimental findings to create a building not only structurally perfect but also harmonious and beautiful. The inner space is very large and high but does not appear as overwhelmingly massive and busy as sometimes in Gothic cathedrals.

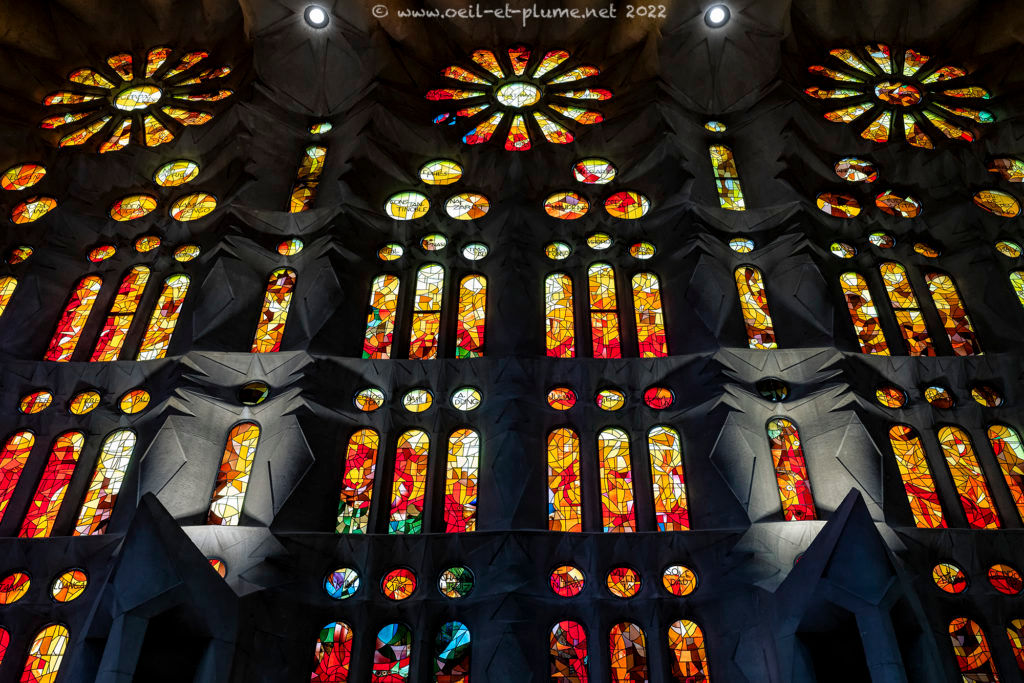

The work on light is also stunning. Tainted glass diffuses delicate coloured light strays and create an intimate atmosphere, in a way reminiscent of gothic style.

I love the stylish sculptures, imposing in size and shape, but again, not massive and over-adorned. A beautiful pipe organ standing proudly behind the altar reminds me of my former profession.

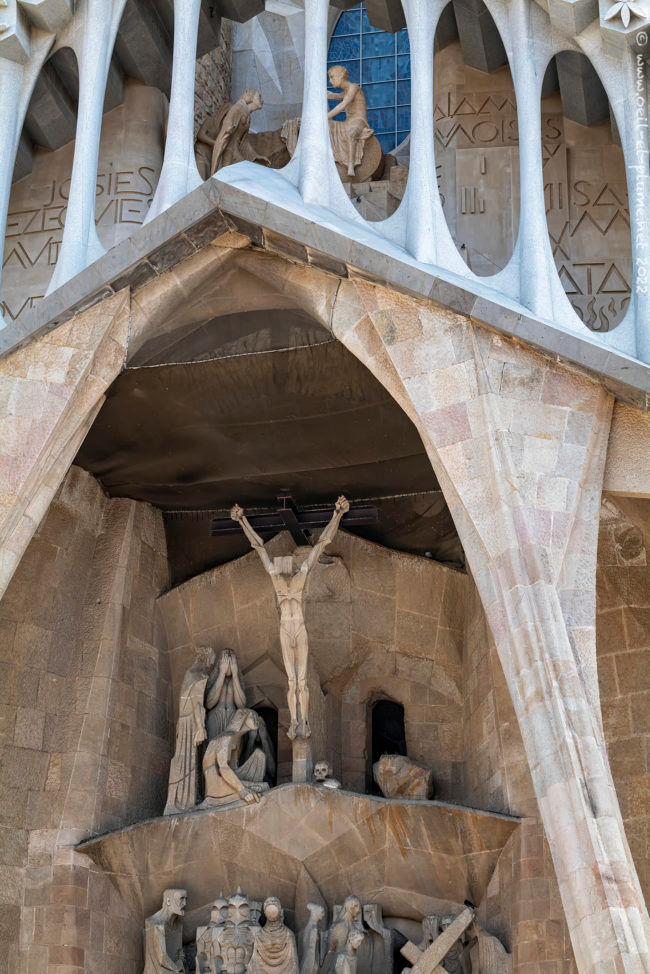

After a long and beautiful visit, we leave the Sagrada Familia through the Passion façade. Contrary to the highly adorned Nativity façade, the Passion façade is austere, plain and simple. It portrays the last moments of the Christ as well as the sins of mankind. Made with ample bare stone, the façade straight resemble a human skeleton. Shadows are equally straight and bold. The body language and particular the facial expressions of the human sculptures express pain, sorrow and distress.

Art historians often praise the unique architectural style of the Sagrada Familia. On my modest end, I can only confirm that such a visit constitutes a milestone in my globetrotting experience. I feel proud of mankind and deeply impressed about Gaudi and all other people who have contributed to such an architectural marvel.

Montaner’s Palau de la Música Catalana

The Palau de la Música Catalana (Catalan music palace) constitutes another architectural gem crafted under the modernist agenda in the early 20th century. Similarly to Gaudi in the Sagrada Familia, Luis Domenech i Montaner incorporated many distinctive features of Catalan arts and handicrafts, and experimented successfully innovative building techniques of his own. However, the general purpose and style of the Palau differ notably indeed. Montaner’s work is characterized here by ornaments inspired in the Hispano-Arab architecture.

I feel so blessed to tune with such a magnificent architectural realisation. Having run upstairs upon the morning opening, I stay in the balconies. On the stage below, the pipe organ distills generously various pieces of religious classical music, filling the space with notes. No organist is to be seen, as the organ is activated electronically. It takes me long until I convince myself to leave.

Epilogue

While this was not my first visit to the Sagrada Familia, I visited the Palau de la Música Catalana for the first time. To me, the Sagrada Familia is simply unique and sublime. The monument is an expression of faith and artistic creativity of a genius who was poorly rewarded during his lifetime by his fellow citizens. The Palau charmed me with its stunningly delicate inner architecture that can only help producing exquisite music. Unlike Gaudi, Montaner enjoyed a prominent social status in Barcelona during his life, not only as famous architect but also as professor in the Barcelona school of architecture and politician.

Both masterpieces of Catalan modernist architecture reflect stunning human cleverness and creativity. Hence an obvious question: Why did such astonishing style decline only a few decades after its birth? Art historians point out that modernist architecture was too expensive to build and not well in line with the overwhelming trend of standardisation that shaped the following decades of the 20th century. My rationality can hear those arguments, while my creativity mourns such rapid decay.

Today’s art displayed publicly in Barcelona is more fragile and ephemeral even, made of running water and light. Those art pieces are beautiful and appreciated as such by large audiences. I trust that our 21th century will produce more compelling and long-lasting master pieces of art.

Cheers,