Many people are familiar with the vibrant town of Chania, located in northwest Crete. Only few are acquainted with the quieter and more rural Akrotiri peninsula. The area entails some natural and cultural gems.

Over the centuries, the deeply Cretan local cultural identity was complemented by classical Greek, Byzantine, Venetian and Ottoman influences. Despite or maybe because of the many foreign influences, northwest Cretans fiercely fought for their cultural identity and their political autonomy.

During the Greek Antiquity, northwest Cretans forged and defended the Minoan city-state of Kydonia, one of the most powerful cities of ancient Crete. In the late 19th century, Akrotiri peninsula headquartered the Cretan Revolt against the Ottoman rule. The peninsula hosts the tomb of Eleftherios Venizelos. The Cretan Greek statesman was instrumental in the creation of a semi-autonomous Crete state in 1898 and eventually its union with Greece in the early 20th century.

Greek orthodox religion is a key component of local cultural identity. Three monasteries are found in the hills to the north of Akrotiri. Dating 17th century, Aghia Triada is beautifully set in olive and orange groves. It was founded by two Venetian monks. Further into the hills, Gouvernetos monastery is built like a fortress, with a large square building surrounding a central courtyard. It is still run by a strict monastic rule.

We enjoyed visiting those monastic infrastructures, but had in mind more secluded locations.

Arkousiotissa cave

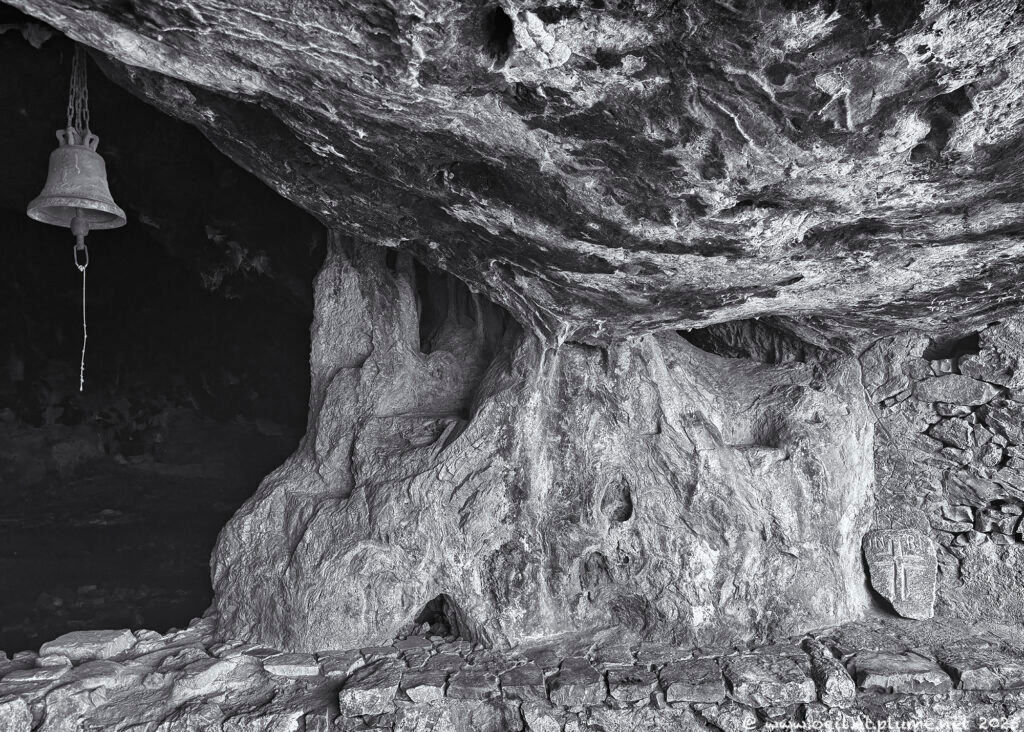

A pathway from Governeto monastery leads to the cave of the Arkoudiotissa, named after a stalagmite resembling a bear. This cave has been used for worship since ancient times as there is evidence for cults of Artemis and Apollo. During the Christian era, it was dedicated to the Arkoudiotissa Panaghia (Our Lady). Ascetics lived in the caves in the area.

One can feel the high energy spread by the fantastic cave architecture complemented by man-made religious artefacts. This unique place tells us without words its complex worship history that well predate Christian rites. We loved the place to the point to visit it twice in two consecutive days.

Katholiko monastery

Further along the path, the Katholikon monastic church is nowadays abandoned. Probably founded by St John the Hermit, it is built into the cliff with a unique church largely carved into the rock-face. Near the Katholikon and deep into Avlaki Gorge, a modest rock cave is believed to be the resting place of St John the Hermit. Saint John arrived to Crete from Egypt in the 6th century.

Overgrown with fig trees, the Kaholikon ruins exhale an undeniable charm. It remains challenging to imagine how a monastic community could have lived autonomously in such remote area. The answer lies probably in its relative proximity to the sea.

Mediterrean sea

In fact, the Mediterranean sea is not far away and calls us to its shore. On the way, Nature is at its wildest. Deep into the gorge, the path weaves in and out between stone walls, erratic rocks, tormented fig, olive and pine trees to find its way to the sun and the sea. Gatekeepers, wild goats monitor our progression with much circumspection tainted with a pinch of curiosity.

We reach the Mediterranean shore of a narrow and rocky bay bathed in emerald-green sea water. Over the centuries, people have landed there and started their in-land progression. They even built a boat shelter to hide and protect their exit route to the sea.

In fact, Akrotiri peninsula was populated from the sea. Due to its geographical isolation and hilly landscape, the area visited was only connected by road to the rest of the peninsula in the 20th century. Early Christians were part of the visitors and settlers during the first centuries of our era.

This is why the first Christian monastery built (Catholikon), close to the sea, much predates the Greek Orthodox Aghia Triada and Gouvernetos monasteries, located higher in the hills.

I remain fascinated by the ability of people in ancient times to penetrate wild environments, to climb steep slopes or rock walls, to build important pieces of religious worship and to experience their monastic lives in such challenging locations. The Gods must feel honoured by their efforts.

Cheers,