In 2011, I crisscrossed Petra for days, leaving no stone unturned in my appetite for impossible rock formations and amazing pieces of rock-cut architecture. This time, the perspective was different: limited time and geographical mobility, but memorable family-enriched exploration.

Rediscovery

As a reminder, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt “discovered” Petra in 1812 during his ambitious quest to trace the source of the Nile River. Disguised as a Muslim sheikh, the Swiss geographer and Orientalist became the first Westerner since the Crusades to set eyes on the ruins of the ancient Nabataean city. Despite the suspicion of the local Bedouins, he managed to visit most of Petra’s main landmarks. By crosschecking his observations with historical sources, Burckhardt identified the site as the former capital of the Nabataeans, later publishing a colourful account of his experience.

Nomadic Arab people, the Nabataeans settled in the region in the 4th century BC. They began building their capital, Petra, with the establishment of their kingdom in the 2nd century BC. They transformed Petra into a major regional trading hub within the network of incense trade routes, which brought them considerable wealth. Adapted to desert environments, the Nabataeans excelled not only in trade but also in agriculture and stone carving. The kingdom eventually fell to the Romans in 106 AD. Devastated by a powerful earthquake in 363, Petra was inhabited until the 7th century, later gradually abandoned until its rediscovery in the 19th century.

Siq

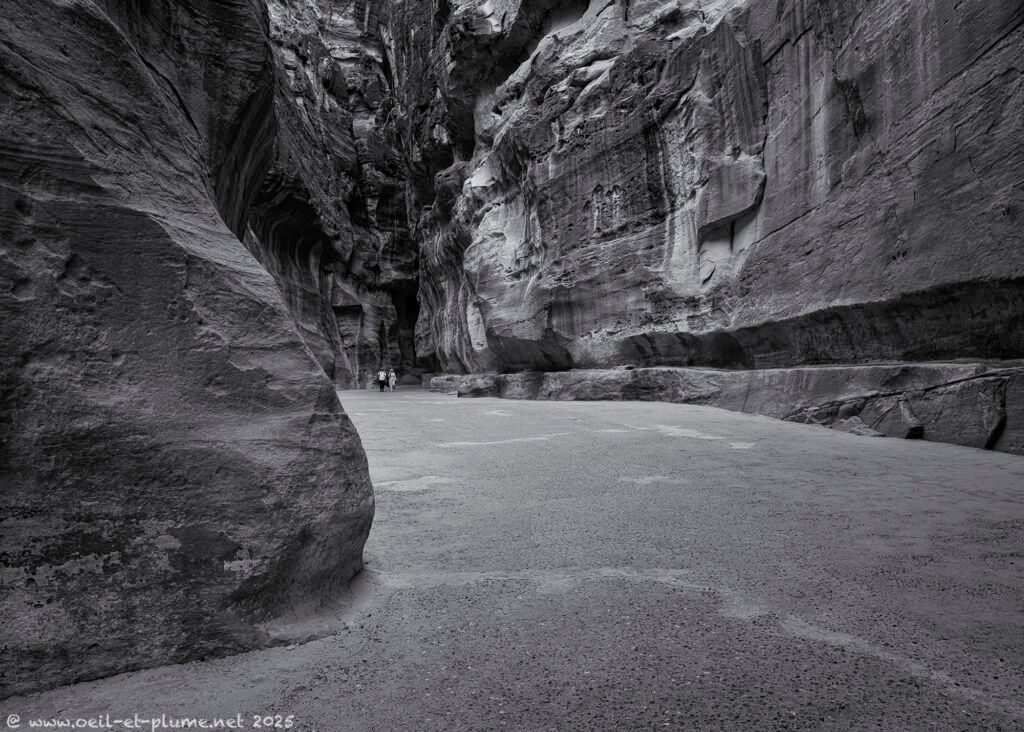

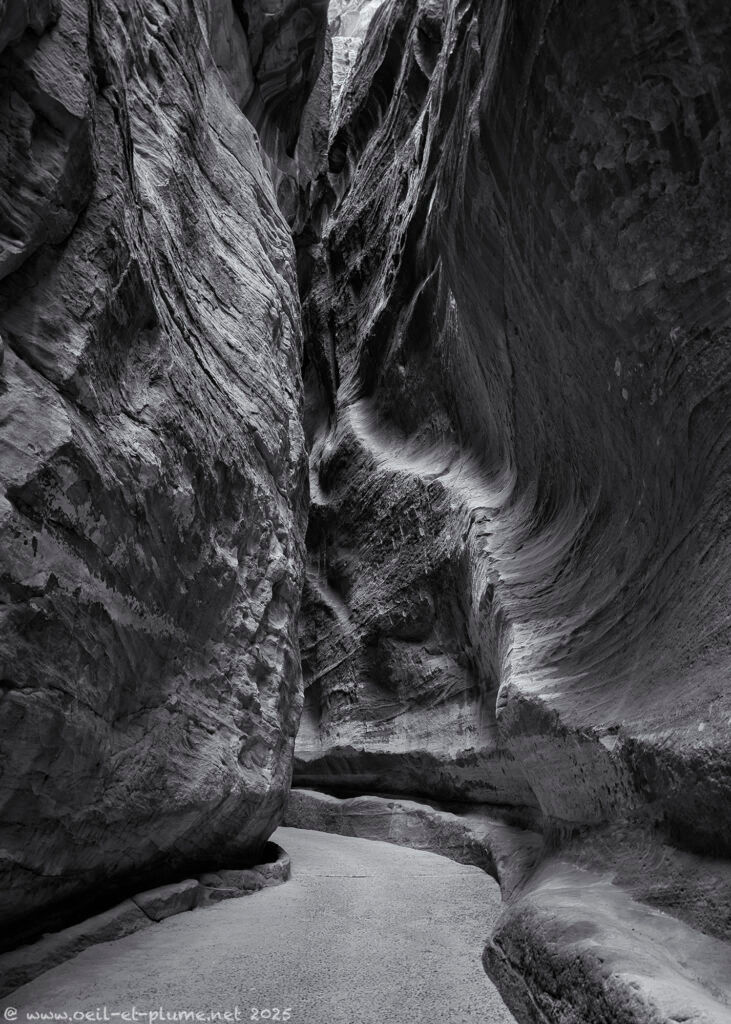

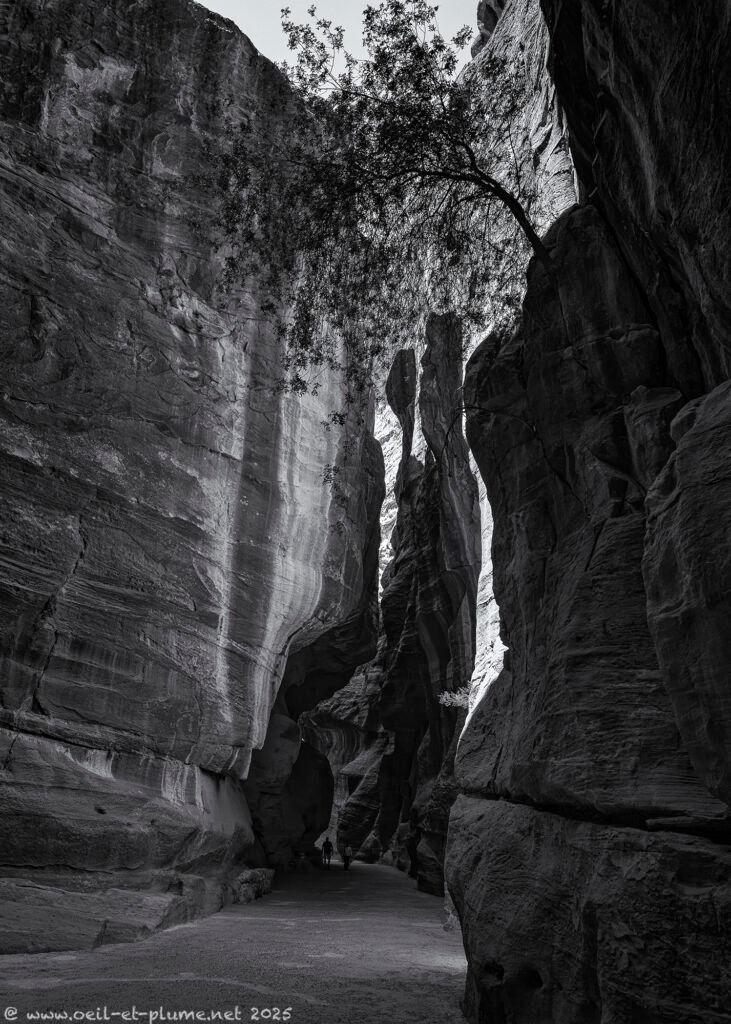

Like Burckhardt, we enter the historical site from the east through the Siq, a dramatic natural shaft. From above, this narrow, winding gorge appears as a thin slit carved into the sandstone plateau. At ground level, the Siq forms a natural waterway leading into Wadi Musa, a geological feature that was vital to Petra’s historical development. My eyes and my mind are captivated by the complex interplay of stark light and deep shadow across the faces of this geological marvel.

After squeezing through an unusually narrow and shadowed passage, the eye struggles to pierce the darkness, the way ahead hidden in mystery. Then, after some distance on foot, a magnificent façade of rock-cut architecture emerges. The Treasury glows in the morning light through the slit of stone like a secret unveiled.

Treasury

Petra is renowned above all for its Hellenistic-inspired architecture. Best exemplified by the iconic Al-Khazneh, or Treasury, the monumental facades of Petra’s tombs display strong Hellenistic influences. This reflects the cultural cross-fertilisation that occurred between the Nabataeans and other major civilisations of the ancient Middle East.

In Burckhardt’s own words:

“An excavated mausoleum came in view, the situation and beauty of which are calculated to make an extraordinary impression upon the traveller, after having traversed for nearly half an hour such a gloomy and almost subterraneous passage (...). The natives call this monument Kaszr Faraoun, or Pharaoh's castle; and pretend that it was the residence of a prince. But it was rather the sepulchre of a prince, and great must have been the opulence of a city, which could dedicate such monuments to the memory of its rulers...”

Nabataean mix

After the decline of the Nabataeans, Petra absorbed further cultural influences, particularly from the Romans and later the Byzantines. Yet its identity remained profoundly Nabataean—deeply rooted in the natural elements of land, rock, and water.

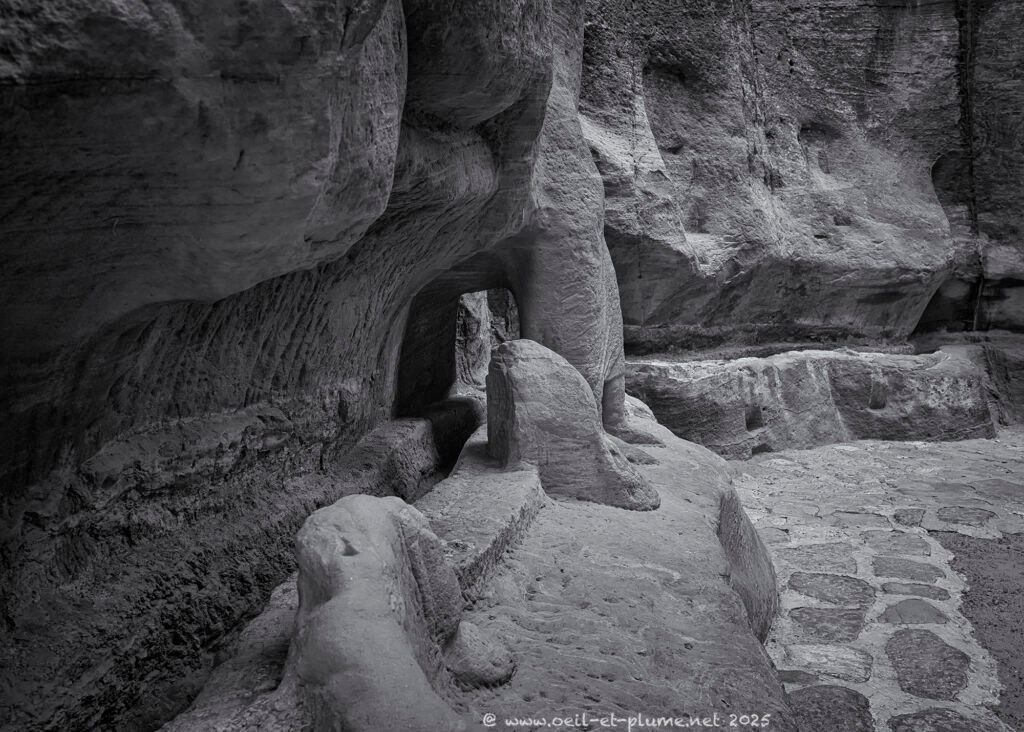

Rose City

The Nabataeans were extraordinarily skilled in carving a variety of structures, buildings, and sculptures directly into the sandstone. Their rock-cut architecture, executed with the simplest of ancient tools, demanded immense labor and precision. The façades of their official monuments often rose on a massive scale, richly adorned with intricate geometric patterns. The sheer size, accuracy, and refined finish of these excavations remain breathtaking. The Nabataeans also played with the natural beauty of the sandstone itself, accentuating its striking veins and ever-shifting colours.

No wonder Petra earned the nickname “Rose City,” its monuments glowing with the ever-changing hues of the sandstone.

High Place of Sacrifice

I was eager to revisit the High Place of Sacrifice—my favorite spot in Petra. Perched atop Jebel Madbah, it offers not only breathtaking panoramic views over the ruins of the ancient city but also a profound sense of emotional and spiritual resonance. Accessible via an 800-step climb, the site remains largely free from the crowds, allowing one to fully absorb its atmosphere.

I reach the rectangular courtyard in the warm, fading light of dusk. The Nabataeans worshipped their deities at open-air high places, performing sacrificial rituals under the sky. Petra’s High Place of Sacrifice was primarily used for the offering of animals to the Nabataean god Dushara. Beside the central low table, an altar was flanked by symbolic stone blocks representing various deities. Adjacent to the altar, a rock platform features a circular basin, likely employed for purification and sacrificial rites. Carved also directly into the sandstone, a drainage system channelled away the blood of the offerings.

I lingered long at the High Place, enveloped by a deep sense of accomplishment. This revisit to Petra now feels fully meaningful, filling me with joy, serenity, and a happiness that will radiate around me for days to come. My descent to the bottom of Wadi Musa is like an ethereal, effortless glide past the scenic Nabataean monuments, each step a gentle journey through history and beauty.

Water is life

With the last light of day, it is time to return to real life. The Siq is already cloaked in night, abandoned by the daytime visitors. Each of my steps resounds, echoing against the towering walls.

I pause to admire the ingenious waterways carved by the Nabataeans, running like veins along the deep gorge. Thanks to their sophisticated carved water systems, the Nabataeans were able to manage the region’s water supply, creating an artificial oasis in Wadi Musa. Flash floods were controlled through dams, cisterns, and water channels; rainwater was carefully collected and stored. This abundant water storage allowed the Nabataeans to endure prolonged periods of drought.

Water lays at the heart of Petra’s grandeur. The Nabataeans’ mastery of water management turned scarcity into abundance and prosperity. Their ingenuity reminds us about the contemporary imperative to respect and manage our natural resources with foresight and care.

Cheers,