Continuing from here.

Living together

Following their military conquest of Hispania in the early 8th century, the Muslim Umayyad rulers developed the economically and culturally vibrant Al-Andalus (Moorish Iberia) kingdom. During the Islamic Golden Age from the 10th to the 12th century, Cordoba became the capital of Al Andalus and a prominent center of education, learning and art.

The prosperous period corresponds also to the Jewish Golden Age in Spain. During this time, Jews and Christians experienced relative tolerance, prosperity, and cultural integration within the broader Islamic society. Jews and Christians took part in the royal court and contributed to the city’s rich intellectual and cultural life.

The Conviviencia (living together) period deteriorated sharply later due to changing policies of the Muslim rulers. The Almohad dynasty forced Christians and Jews to convert, and forced Muslims into their interpretation of the faith. In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Reconquista (reconquest) by the Spanish Christian monarchy marked a turning point. Iberian Jewish and Muslim people were strongly discriminated and forced to convert to the Catholic faith. Those resisting religious conversion faced death or expulsion from the Spanish Kingdom.

Architectural fusion

The Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba best illustrates the distinct intercultural dynamics of both the Convivencia and Reconquista periods in Andalusia’s Middle Ages. The location hosted first an early Christian church, that the Moorish replaced by a mosque in the 8th century. Following the fall of Cordoba to the Spanish troops in the 13th century, the mosque suffered some damages. A cathedral was erected eventually, integrating the remaining structure of the mosque and adding Roman, Gothic and Renaissance architectural elements.

The present structure of the Mosque-Cathedral reveals a captivating architectural fusion. It both contrasts and interweaves cultures, faiths, and styles. To me, it feels far more like a mosque than a cathedral—and I find that deeply compelling. In many respects, the Muslim-Moorish character outweighs the later Christian imprint. Yet the two coexist in a dialogue that softens their differences. Ultimately, these seemingly disparate elements complement one another, merging into an impression of remarkable harmony and beauty.

Artistic creativity

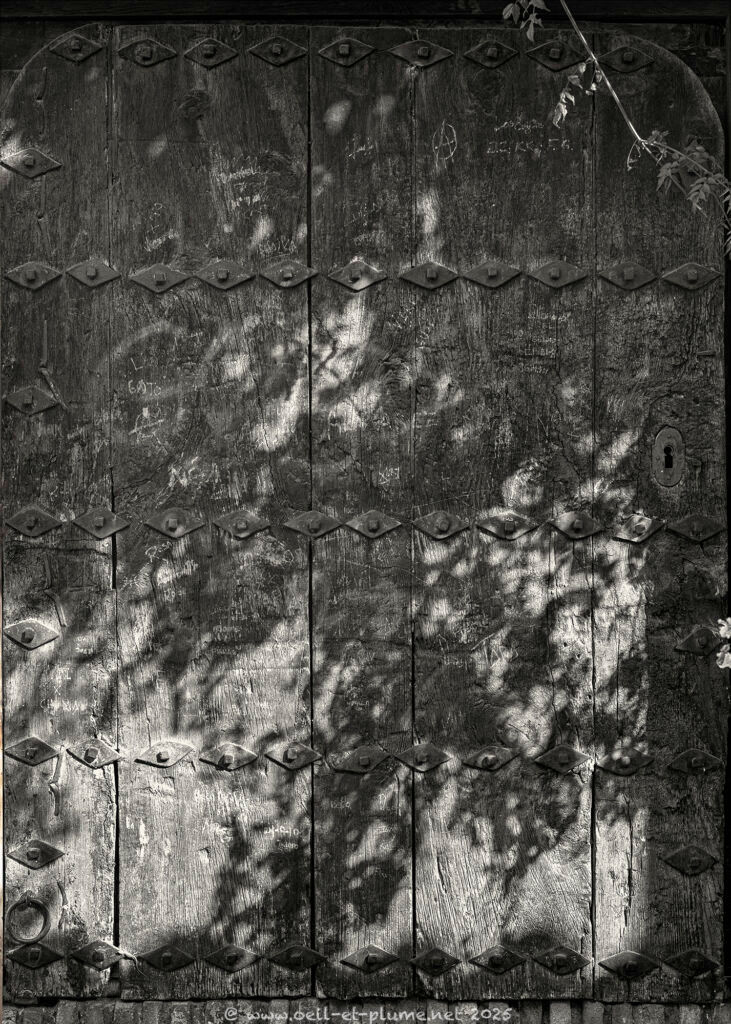

Moorish cultural legacy is not confined to monumental sites like the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba. It reveals itself just as clearly in humbler corners of daily life—in old water systems and neighbourhood wells, in arches and courtyards of modest houses, in the patterns of Andalusian handicrafts, ceramics, and textiles. More profoundly, it lingers in gestures, sounds, and habits that shape the everyday rhythm of local people.

Moorish cultural legacy in Andalusia is not confined to monumental sites like the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba. It reveals itself just as clearly in humbler corners of daily life—in old water systems and neighbourhood wells, in arches and courtyards of modest houses, in the patterns of furniture items, handicrafts, ceramics, paintings and textiles. More profoundly, it lingers in gestures, sounds, and habits that shape the everyday rhythm of local people.

So pervasive is this Moorish legacy in Andalusia that the eye and mind often struggle to separate the Moorish from the Christian or the Jewish, and misses to distinguish antiquities from contemporary creations. Everything seems to merge, to flow, to belong. And ultimately, the quiet beauty and seamless blending of those various cultural legacies are what speak most deeply to the heart.

Cultural resilience

As recalled above, intercultural encounters are not all harmony and beauty. They entail power interplay, rule imposition as well as political resistance and cultural resilience. This power game happened in Andalusia as well, especially during and after the

Reconquista in the 14th and 15th century.

The Catholic Inquisition took a major role during that period, which prompted many forced religious conversions across Andalusia amongst Jewish and Muslim people. Some of them paid a lip service to forced conversion to stay and survive, while practising their original faith in secrecy at their homes. Contemporary archeology identified some Jewish residences in Ubeda equipped with an underground synagogue and an ablution bath.

Under a stormy sky lightening the Alhambra in old Granada, I wonder whether I would be capable of such cultural and religious resilience today: probably not. The heavy rain cuts short my existential reflection. What about you?

Cheers,