Monastic life

I have been always puzzled by the seclusive character of monastic life which aims to strictly limit social interactions, especially with the outside world, to better connect with God. While I respect such lifestyle when it is freely chosen, I strongly believe that human beings are fundamentally social subjects, regardless of their religious beliefs.

You may remember Archimandrite Ioustinos, the venerable Greek Orthodox priest and lifelong caretaker of Jacob’s Well in Nablus in the north of the West Bank. He must have felt lonely at times in the course of his religious duties. Yet he remained connected to his social environment.

The West Bank and the Jordan Valley also remind us of more seclusive religious choices, as they host many historical Greek Orthodox hermit monasteries. Often called lavras, these monasteries historically consisted of communities of monks living in remote and hard-to-reach locations. In the first centuries of our era, hermits lived in isolated cells—often natural caves—situated near a central church and a refectory. Since their inception in Byzantine times, the lavras have morphed into elaborated monasteries while remaining firmly focused on prayer and detachment from the world.

I visited three Greek Orthodox hermit monasteries in the West Bank recently. Built into the cliffs of the Mount Quruntul overlooking Jericho, the Monastery of the Temptation is the best known, as it is believed to be where Jesus fasted for forty days. My photographic eye and my soul found the other two monasteries more compelling.

Overlooking the Kidron Valley between Bethlehem and the Dead Sea, the Monastery of Saint Sabbas occupies a dramatic and austere landscape. In the 5th century, Saint Sabbas founded a lavra on one side of the gorge, which later led to the construction of the Greek Orthodox monastery on the opposite side of the valley. Also known as Mar Saba, the monastery is renowned. Saint Sabbas formulated here a set of rules that later shaped the monastic life and liturgical order known worldwide as the Byzantine Rite. Mar Saba is one of the world’s oldest monasteries to have been inhabited almost continuously, and it preserves many of its ancient traditions to this day.

Knocking the main door of the monastery, I was told that no visitor was unfortunately allowed to enter the site on that day. Never mind. Mar Saba impressed me with the barren beauty of its religious architecture and its stark, mineral environment. Resembling a military fortress, it stands defiantly against all possible threats, as if to better enable spiritual contemplation and discipline. In this place, as in other lavras across the world, Greek Orthodox monks have embraced extreme solitude, tempered by forms of communal life—through church services and collective work—designed to meet both their religious aspirations and their human needs.

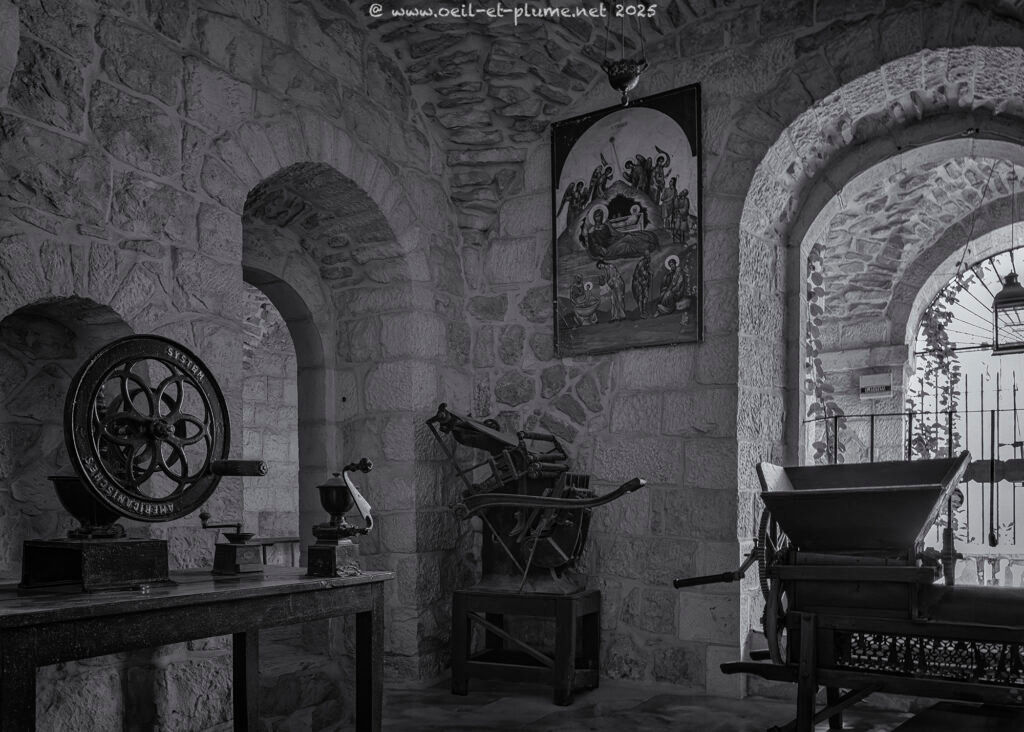

Also known as Mar Jaris, the Monastery of St George is located in Wadi Welt between Jericho and Jerusalem. Clinging to the rocky walls of the scenic canyon, it was built around a cave where tradition holds that prophet Elijah lived for a time, fed by raven. In the first centuries AD, Greek Orthodox hermit monks inhabited the surrounding rock caves, seeking a life of faithful seclusion. A monastery took shape in the 5th century under the guidance of the monk Gorgias of Koziba. Over the centuries, the religious site was repeatedly destroyed and abandoned, only to be rebuilt again. Initiated in the 19th century, the present structure remains an important pilgrimage site to this day.

I was warmly welcomed at Mar Jaris, along with other visitors. The site’s ambient spirituality was enhanced and enriched by the genuine hospitality practiced by the small religious community residing there. The internal monastic rules appeared less strict than those observed at Saint Sabbas, where for instance female visitors are not allowed inside the monastery.

Festive life

At the end of the year, many people seek a festive way of life. In the West Bank, Palestinian celebrations are diverse, drawing primarily from Muslim and Christian traditions. Christmas, celebrated on 24 and 25 December, holds a special place across monotheistic cultures, even though these dates correspond specifically to the Gregorian calendar used by Roman Catholic Christians. Greek, Syriac, Coptic, and Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, by contrast, celebrate Christmas on 6 and 7 January, in accordance with the Julian calendar. In the Holy Land, nothing is ever simple.

Since 2023, Palestinian festivities have been put on hold in solidarity with, and in grief over, the situation in Gaza. This year, however, Christmas celebrations are gradually regaining some momentum and vibrancy. I was lucky—and happy—to encounter a Santa Claus couple in the centre of Ramallah. Yes, Mr and Mrs Santa Claus, riding in a horse-drawn carriage and distributing sweets and small gifts to local children.

The tradition of Santa Claus is rooted in the historical figure of Saint Nicholas. Nicholas was born in Patara, near Myra in modern-day Turkey in the 3rd century. Much admired for his piety and kindness, St. Nicholas popularity spread over time and across the continents; he became known as the protector of children and sailors.

The Santa Claus couple did not stay long in Ramallah. They soon set off for the place to be on Christmas Eve: Bethlehem. I found them there, crisscrossing Manger Square beside the Church of the Nativity, fully engaged in their traditional duties. Santa Claus watched over the installation of a giant Christmas tree and a traditional Nativity crèche. All good, ready for the Christmas festivities.

By early afternoon on 24 December, Bethlehem is already in a state of ebullition. The streets of the old town are packed with scout bands dressed in costumes inspired by Scottish tradition—a probable legacy of the British Mandate over Palestine (1920–1948). I have loved these bands, less for their thunderous music than for the visual spectacle of their martial march. You may agree or disagree based on the video footage enclosed and my still photography below. In any case, who would have expected such scene in Bethlehem?

As daylight draws to a close, the Christmas festivities pause to better prepare for the Christmas Eve. The evening gives way to warm family gatherings around a shared meal, followed by the exchange of gifts. Santa Claus was kind enough to prepare an exquisite present for me.

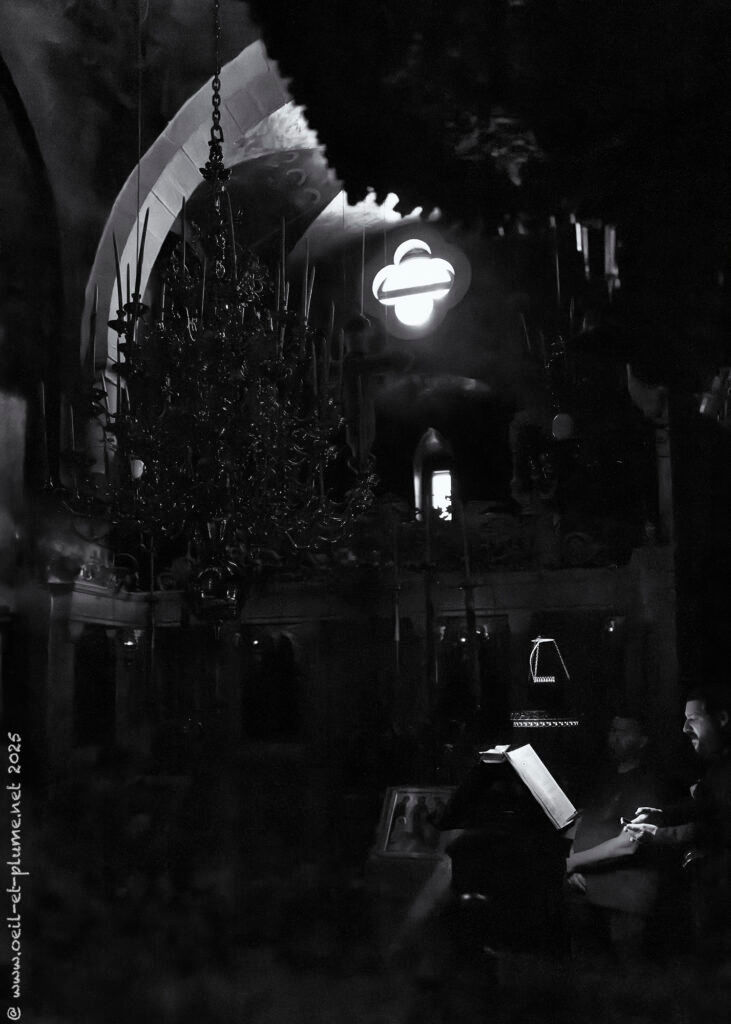

The Christmas religious services start at midnight In the Church of Nativity, gathering a packed crowd including religious and political figures, diplomats and other officials. I prefer more intimate atmosphere. The religious complex entails several underground chapels, were masses are performed from midnight to dawn.

Candid and sweet on the surface, Christmas celebrations invite us to reflect on everyday life—on self-esteem, social values, personal achievements and challenges as well as, perhaps, a deeper sense of spirituality. Merry Christmas!

Cheers,