Rather than visiting Khiva, the third major medieval site in Uzbekistan after Bukhara and Samarkand, I head to Margilon – a small town located in Fergana Valley close to Kirghizstan. One important branch of the Silk Road transited through the Fergana Valley. Margilon hosts what is said to be the last traditional silk factory in Central Asia.

Silk in ancient China

Legend has it that silk was first discovered by Empress Hsi Ling Shi, wife of Emperor Huang Ti (also known as Yellow Emperor, 26-27th century BCE). One day when she is drinking tea under a white mulberry tree, a silk cocoon falls into her cup and starts unravelling. Charmed by the scene, the empress soon develops silk farming (sericulture) and invents the reel and loom as spinning and weaving tools.

We know with more certainty that silk fabric is initiated in ancient China, possibly as early as 3,500 BCE, thanks to the mulberry silk moth native to China. Luxury item, silk goods are initially reserved to the emperor and his family, but spread gradually across the empire.

For more than 3,000 years, the Chinese emperors keep the silk fabrication process in utmost secrecy and retain a near monopoly over silk production and distribution in their empire. Death penalty sanctions anyone smuggling eggs, cocoons or silkworms out of the imperial borders.

However, silk production materials spread in Korea and Japan respectively in the 2nd century BCE and the 3rd century CE. They do not reach the Mediterranean basin until the 6th century CE.

Silk Road

Meant to boost China’s international trade, the Silk Road connecting with the Mediterranean basin will also disseminate Chinese productive techniques.

Chinese silk textiles reach Persia, Middle East and Europe in limited quantities in the 2nd century BCE through various overland and sea routes. Over time those trade routes develop in what is known today as the Silk Road. Silk soon becomes one of the most desirable luxury goods in European Antiquity. Traded at very high prices, it is often more expensive than gold.

The development of the silk-related international trade is very profitable to the Chinese empire because of its near monopoly over production. Controlling key overland routes of the Silk Road between China and the Mediterranean Sea, Persia benefit also greatly from the silk trade before developing its own production capability.

Mid-6th century CE, the Byzantine court in Constantinople is very fond of luxury goods, including silk. The Emperor Justianian I plans to break the silk production and trade monopolies enjoyed respectively by China and Persia through the creation of an indigenous productive capability in his Empire.

In 552 AD Justinian I tasks two Orthodox monks to bring covertly silk eggs from China. The two monks are just back from a long journey in the Chinese empire where they witnessed the entire production process of silk.

Once again in China, the two monks manage to acquire and bring back in Constantinople silk eggs or young larvae in their hollow bamboo walking sticks. They would have carried a few mulberry shrubs as well. In any case, the preferred food of the silk larvae reach Constantinople at that time. In parallel, Justinian I imports silk production techniques from Persia.

Justinian I manages thus to curb the Chinese and the Persian silk near monopolies, only to tightly control later the Byzantine silk production and distribution in his own empire.

The Byzantine silk increasingly supplies the high-end markets in medieval Europe, whereas silk production starts in Arabic countries in the 7th century. Constantinople’s supremacy in the Mediterranean basin falls apart during the 12th-century crusades, when Byzantine silk productive equipment and skilled labour force are seized and forcibly installed in Sicily…

Silk in Uzbekistan

Silkworm breeding and silk weaving was initiated in ancient times in Fergana Valley. Uzbekistan ranks today as the world’s third silk cocoons producer after China and India. Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991 favours the resurgence of traditional crafts such as silk dyeing and carpet weaving, which were restricted under Soviet rule. Matter of national pride, the silk production sector in Uzbekistan remains under strict governmental control.

I visit Yodgorlik silk factory in Margilon twice to document silk production. My first glimpse on the main weaving room, silent at that time, only sharpens my interest to comeback during working hours.

The productive process is displayed and explained to the visitor in guided tours. Techniques are almost those prevailing 1,500 years ago. Before starting the visit, a few words on silk worm breeding.

Silk cultivation

The highly valuable silk cocoon is produced by the mulberry silk moth to protect its larval stage during which the larva (caterpillar) turns to moth.

Wild silk is produced by the silkworm (bombyx mandarina) living freely on the mulberry tree. Commercial silk is obtained through breeding silk larva of the domesticated silkworm (bombyx mori) with mulberry leaves in a controlled environment to harvest silk cocoons eventually.

The tiny eggs of the silkworm are incubated about 10 days until they hatch into larvae. Once hatched, the larva is fed with mulberry leaves to reach soon 50,000 times its initial weight within 5 to 6 weeks.

In order to prepare its future mutation into moth, the silk larva stops eating to spin a protective silk cocoon through eight-shaped continuous body motions. About 1 km to 1 mile of silk thread is so produced within a few days.

Once ready for another life phase, the insect bores a hole through the silk cocoon to mute from caterpillar to moth. By doing so, it breaks the silk threads into multiple segments. This was happens in the wild for the bombyx mandarina. In turn, bombyx mori larva is silenced with heat before that stage to preserve the integrity of the silk cocoon.

Silk fabric production

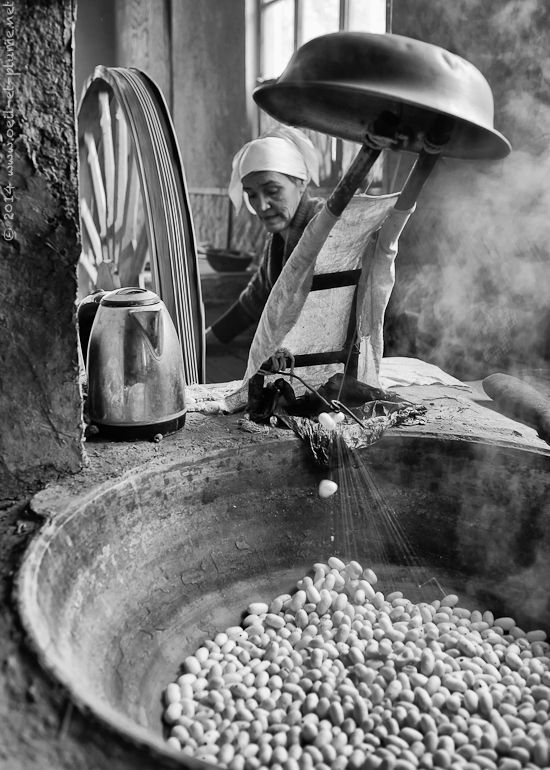

The silk cocoon containing the larva is plunged in boiling water, which kills the larva aand softens a protective substance (sericin) enrobing the raw silk thread. The silk filament is then unbound from the cocoon by unwinding (reeling) the filaments from a few cocoons at once, in order to create a single strand.

Later, raw silk is twisted into strands, and then into yarns able to resist weaving or knitting.

Now clean and soft, silk is ready for dyeing. The design pattern is sketched by seasoned silk workers on future silk cloths and then dyed. This critical phase of the productive process can be quite lengthy, as each colour requires its own dyeing cycle with the material transiting back-and-forth between the design room and the dyeing workshop. Up to eight different colours are used on a single silk cloth in Yodgorlik silk factory.

Contemporary commercial silk is mostly dyed with chemicals. Yodgorlik silk factory relies mostly on natural dyeing substances which include indigo, onion and pomegranate peels, nut bark, acacia flowers. Alun is used to fix the dyes on the silk.

Unbound, the silk yarns are carefully prepared for weaving.

Lucky me, weaving is in full swing in my second visit to the women workshop. These highly skilled female manufacturers evoke me virtuoso organists. Manual looms comprise between 4 and 9 pedals, in addition to the various handles. Challenging motion coordination and multitasking… Up to 8 meters silk fabric can be woven daily by one worker.

Weaving can take many different forms, according to the desired design and quality of the silk material. It can reproduce a design on one or both faces of the fabric, and use various materials. In Uzbekistan, 100% silk fabric is called atlas, while adras mixes silk with cotton. You guessed rightly that the most valuable piece are made of pure silk and designed on both faces…

I pay also a quick visit to the mechanised workshop of the factory. Much less appealing scenes, with noisy Soviet-era machines dictating the production tempo to workers.

Yodgorlik silk factory entails a silk carpet-making and an embroidery workshop. You better be very, very meticulous and patient at work there. One carpet can take more than a year to make. No, I did not ask for prices…

Silk market

Delighted by my visit in Yogorlik silk factory, I do not miss to check the silk goods sold in Margilon’s main market. No surprise, the main textiles sold are cotton-made, as Uzbekistan is also one of the main world’s cotton producer. I suspect many of the affordable textiles are imported from China, as elsewhere in the world.

Fortunately, textile handicraft is to be found in Margilon market as well. Embroidered clothes and hats are still valuated in Fergana Valley, including from younger generations.

But where are the pieces of silk fabric that I admired in Yogorlik factory? Here they are. Beautiful Indeed, altough not quite matching my own clothing taste. The smile of one of the female seller reminds us that silk is worth gold…

Visiting a traditional silk factory located on along the Silk Road conclude beautifully a fascinating journey in Central Asia. Hopefully the traditional silk production will resist the erosion of mass-consuming textile industry. In Margilon, the Yogorlik factory is doing apparently well, better than mechanised silk factories.

There are unfortunately also gloomy aspects of traditional silk production.

One issue concerns the fact that the domesticated silk larva is boiled or steamed alive to preserve the silk cocoon. Animal rights organisations denounce the process and advise to produce and buy spinned wild silk instead – a lighter and softer but much rarer and more expensive material.

Another issue refers to the way silk cocoon is being produced. In Uzbekistan, local farmers are provided annually with small quantities of mulberry silk eggs or larvae to breed. The process is time-consuming and financially poorly rewarding. Moreover, farmers would be strongly incited to cultivate silk worms, otherwise they could be discriminated in other domains of their activity.

These are genuine ethical and political dilemmas, indeed. If you love luxury seafood and don’t bother lobsters being boiled alive for your food enjoyment, the cultivated silk cocoons should not trouble you either. Considering that any governmental policy uses a mixture of carrot and stick to promote the public interest, the second concern should be of limited scope.

Up to each of us to draw a line and conclude.

Cheers,