Travelling in Ethiopia brings quickly the striking evidence of a very culturally diverse country, structured mostly along ethno-linguistic lines. There are about ninety languages spoken in Ethiopia.

Most Ethiopian people speak Afro-Asiatic languages belonging to the Cushitic or Semitic branches. Their cultural traditions are influenced by various civilizations from the Horn of Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and India. The Cushitic branch includes mainly Oromo, Konso and Somali people; the Semitic branch comprises Amhara and Tigray people.

Many tribes of the Omo Valley in southern Ethiopia speak languages belonging not to the Afro-Asiatic but to the Nilotic linguistic family. Ethiopia’s Nilotic communities are culturally more connected to South Sudan and the African Great Lakes. Amongst them are the Hamer, Karo and Mursi.

I spend ten days in the lower part of Omo Valley last month to visit four emblematic local tribes – the Konso, Mursi, Karo and Hamer. Upon my request, my guide brings me deep into their respective tribal land to stay in rarely visited villages. A great experience.

Konso governance

‘Let’s visit the Konso king this morning’. My guide’s proposal surprises me. Why would a Ethiopian tribal king receive a farangi (foreigner) dotted with noting but his curiosity to learn about the Konso tribe ?

The question remains largely unanswered to date. However, the encounter is very agreeable and enriching. As expected, the Konso king nurtures a sense of decorum, dressed in the most colourful Konso attire. Rather surprisingly, he is young, down-to-earth and very friendly. I will remember his generous laugh and smile forever!

Kala Gezhgne studies and practices civil engineering in Addis Ababa until the death of his father twelve years ago, which prompts him to take over the Konso royal duties. Konso kingship is a family matter since 22 generations. He is also the chief of one of the nine clans of the tribe. Not to mention his charge of chief priest (poqola).

A simple dirt and rocky road leads to the Konso royal compound located in Kala sacred forest, at some distance from the Konso villages. On the way, the forest looks like a natural park, full of untapped wood resources including century-old trees.

Close to the royal compound, a modest cemetery hosts the deceased Konso queens. In turn, it takes 15’ walk deep into the forest to reach the kings’ resting place.

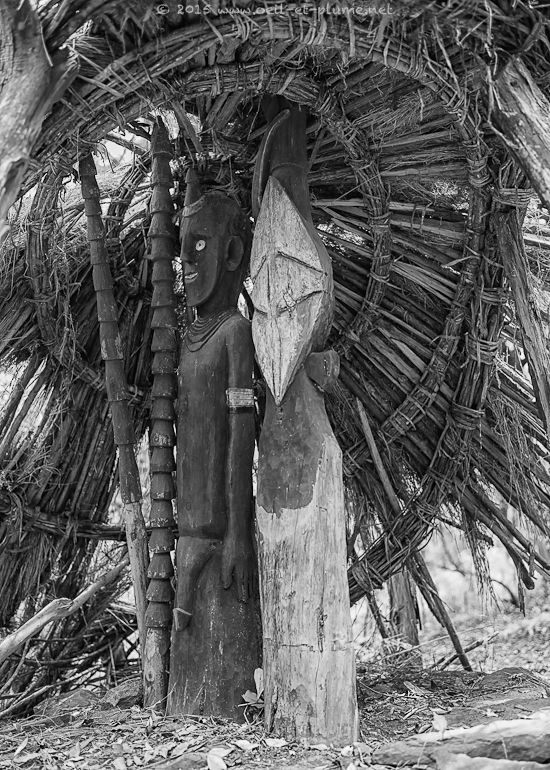

Here rests Kala Gezhgne’s father. A Konso king or clan chief tomb is signalled with wooden totems (wagas) covered with a vegetal hut.

The royal tomb is recent – about three years old only. Upon their death, Konso kings and clan chiefs are mummified for nine years, nine months, nine days and nine hours before their burial in a symbolic reference to the nine Konso clans. During the interim period, mummies are conserved in a simple hut and displayed in special occasions.

Other members of the royal family are buried is a special place located outside of the sacred forest.

Konso people traditionally worship a deity named Waaq in a form of monotheistic faith typical of Cushitic tribes. Nowadays, about a third of Konso people still practice their traditional faith, while half of them are Christian Protestants and the remaining minority Ethiopian Christian Orthodox.

The royal compound does not distinguish significantly from other Konso homes let aside its considerable size. No obvious sign of wealth or social status is displayed to the visitor. However, the place offers beautiful traditional sceneries. The senior lady hereafter is the Konso queen, mother of my royal interlocutor.

The Konso tribe counts some 250,000 members, of whom about 235,000 individuals living in Konso territory in the Great Rift Valley. Konso represents one of the administrative districts (woredas) of Ethiopia’s Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region.

Living aside his people, the Konso king relies on informants and messengers to stay tuned wit his community. His ruling mixes traditional mechanisms and modern procedures. ‘When it comes to dispute settlement, the Konso traditional system is much more effective than the modern legal system’, states Kala Gezhgne.

Konso traditional mediation system is complex, consisting in a five-tier structure. Friends, family, neighbourhood and clan represent the first four successive mediating bodies. Unsettled cases are brought finally to the king whose decisions are authoritative.

We live now Kala Gezhgne to visit his home town Gamole.

Gamole

Gamole is one traditional Konso settlements defined as part of world’s cultural heritage by the Unesco. For protective purpose, the town centre is perched on a hilltop and circled by concentric massive basal walls.

The outer walls count several main gates. Those gates lead to key locations of the town such as squares and collective buildings. Living the settlement, they connect with water points, local markets or farming land.

Once the first city wall crossed, we follow the tortuous footpath to reach soon a mora. The communal house hosts young male adults who sleep there and provide community services such as ambulance and fire brigade.

In normal times, moras are more a locus for social gathering and leisure. The youngsters whom we meet in front of the collective structure are busy with lamameta game, played on a wooden board with seeds.

A Konso settlement counts several moras inter-connected by footpaths. Moras are mostly built on the side of public squares where recreational activities, as well lawsuits and religious ceremonies are performed.

Public squares nearby moras usually exhibit high generation trees (ulahitas). Cut by the ritual priests in the sacred forests, generation trees are erected to represent the achievements of the successive generations of local residents.

One trunk is usually added to the generation tree every 18 years. Summing up the number of trunks erected across the town, Gamole is more than 800 years old.

Ritual stones lie on the ground of the public squares for various purposes. Some of those big boulders are thrown by young adults as far as possible to demonstrate their physical strength and hence their adulthood. Others are the locus and the memory of public oaths. Others are ritual spear sharpening stones.

Within their walled town, Konso people live in a compound fenced with wood and stones. Typical Konso homestead counts five to six thatched structures made of wood and mud. Settlements are quite densely built, which makes them prone and vulnerable to fires.

I feel so happy about this fascinating visit. But I need to meet more people. Moving from one ward to another, we cross local residents on the sinuous footpaths, venture into private yards.

We end up in the local beer pub where many males are gathered. In a matter of a few seconds, I become the focus of the customers. I resist diplomatically but firmly to various offers to drink a calabash of local beer.

All pieces of information that I disclose about myself are commented and often hotly debated. My personal profile is so weird to them that a guy concludes that I am fabricating myself an odd identity to confound them. I simply smile back.

Time to leave now. Gamole counts three concentric outer walls, reflecting the historical development of the settlement. From the town centre on the hilltop, the slopes were progressively terraced to house new generations.

According to Konso tradition, the elder son of each household stays in his family original homestead while the cadets move out to build their own homes further downhill. After a while, new homesteads form new ward, requiring an additional outer wall.

Konso economics

On the next day, we head to a Konso market where people attracting people from all over the region. I spot in the colourful exuberance the green touch of moringa. Once cooked and sometimes mixed with sorghum, the leave of a local tree resemble spinach, a key and very popular food in Omo Valley. Moringa is reputed to have also many medicinal virtues.

In the butchery section, several goats have been just slaughtered. Their blood is collected to be added to local sorghum beer. The mixture is consumed on the spot. I am presented a calabash of this very rich drink: no thank you.

Konso society is heavily agricultural, famous in the Horn of Africa and beyond for its mastery of irrigation and terracing of mountain slopes. It is only marginally pastoralist, raising cattle, sheep, and goats.

Hard-workers, Konso farmers often mix up staple crops (e.g. sorghum, corn) and cash crops (i.e. cotton, coffee) on their arable land to mitigate the risk of a bad harvest affecting one of their agricultural outputs.

Last but not least, Konso look at trees to hang up bizarre wooden devices. What are they for?

They are beehives, made of hollow wooden trunk sections. Hard-working farmers, Konso people of Omo Valley realise and present superb open-air exhibitions of abstract art.

Cheers,