After our farewell with the Konso people in the Omo highlands, we descend into the bottom of the valley. The Lower Omo Valley beautifully combines various ecosystems including volcanic outcrops, grasslands and riverside forests hosting a wide diversity of wildlife.

In fact, my primary interest to visit Lower Omo Valley is to meet with the Mursi tribe.

The Mursi are a Nilotic pastoralist ethnic group counting some 7,500 individuals in Ethiopia. Mursi people are mostly animists, worshipping a deity called Tumwi that they locate in the sky.

Surrounded by mountains between the Omo River and its tributary the Mago, the Mursi live in an isolated region close to the border with South Sudan.

We enter the Mago National Park, driving a long way deep into the semi-arid protected territory. How much protected? ‘There is much wildlife poaching going on here.’ confesses my guide. As a matter of fact, we don’t cross any wild animal on our way.

Communal life

We reach the Mursi village late in the afternoon. I wonder how my guide and my driver found this small settlement lost and hidden in the bush.

After the usual greetings with the village chief and the elders, we set up our tents next to their huts and prepare for the night. Our stay sets the village into a special ambiance, as it is uncommon for them to host a foreigner.

After dinner, my guide entertains the villagers with stories, video clips and music stored in his smart phone. The audience comments and laughs loudly, in a Saturday night fever mood.

The night is wet, prelude to the rainy season that is about to start. I wake up at dawn with my mat floating on a small pond of water. I get up quickly to enjoy the soft light and the strong smells of the soil watered by the rain shower.

Mursi herdsmen are already preparing or guiding their cattle to the grazing grasslands.

Essentially pastoralist, Mursi tribesmen engage into farming only periodically and marginally, banking on the seasonal floods of the local rivers. The village life is largely communal, sharing the output of their cattle.

After breakfast, the chief representative leads us to village. Mursi chiefs are usually the most respected elder in a village and can be removed. We tour the wooden and mud huts starting with the elderly people. Most men have gone already, leaving women and children at home.

Female body art

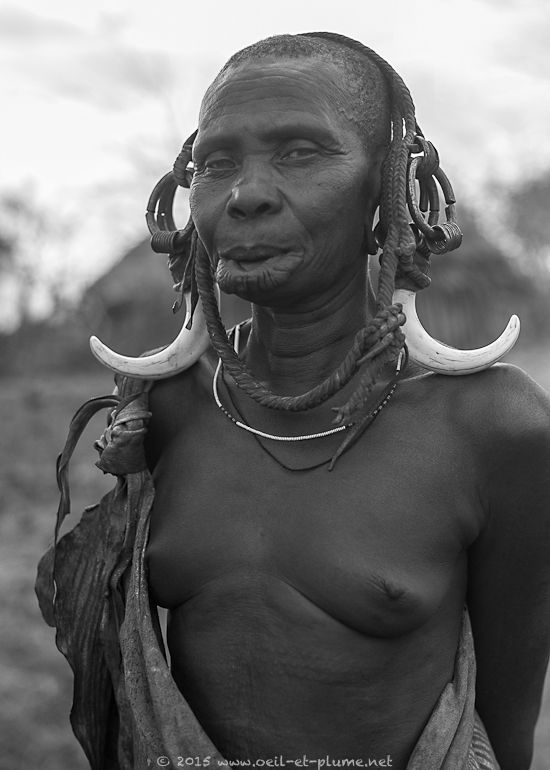

Mursi women are worldwide famous for wearing lip plates. Occasionally, they also paint their bodies and face in white.

At the age or 15 or 16, most Mursi women have their bottom teeth removed and their bottom lips pierced. Once healed, the lip cut is progressively stretched through the insertion of a wooden peg first, replaced soon by clay lip plates of increasing sizes. Women craft and adorn their own plates that can reach a final diameter of 20 cm.

Traditionally, Mursi women wear lip plates to beautify themselves ahead of their marriage. The larger the clay plate, the more the woman is worth to be married. Tradition has it that clay plates were first used to prevent capture by slave traders.

I feel odd at the sight of those overstretched lower lips over-streched with their clay plates and even more looking at falling lips void of their circular support.

Mursi lip plates strongly remind me of the long-neck Padaung women in eastern Myanmar, whose neck are progressively extended by metal laces until their neck muscles are unable to support the weight of the head without their metal support.

Unlike Padaung women, Mursi females only wear their lip plates for a short time for convenience and comfort. They do so for special moments in the communal life.

Nowadays, Mursi girls can often decide whether or not to wear a lip plate. A growing number of them reject this practice.

I am fascinated by the body scarification displayed by Mursi women – another of their beautification methods. They slice their skin with a blade after lifting it with a thorn. The piece of skin left over becomes scar eventually. I well imagine how painful those adornment rituals are.

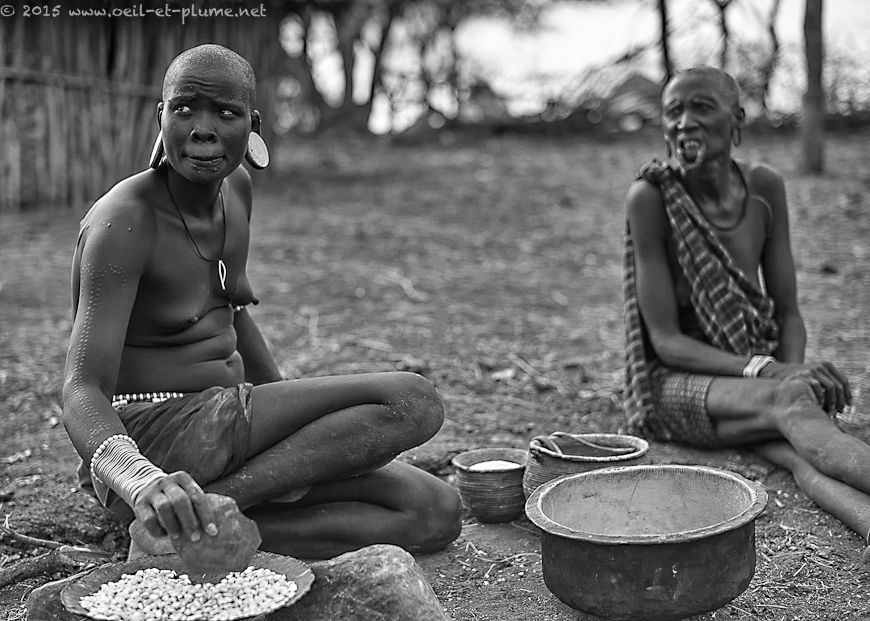

We enter the hut hosting an old woman who is milling sorghum for her meal. Stone mills are the norm in the region. Females spend quite some time daily on their stone mills.

Approaching another hut, I spot a beautiful women also milling crop – an iconic scene. With a wealth of smiles and hand gestures, I manage to photograph her across the door.

Male body art

And what about the Mursi males? I did not meet many of them during the day, except for the elderly unable to take care of the cattle. Late in the afternoon, this guy accepts posing for me in a very male posture.

Mursi men also use white paint for their bodies and their faces in special occasions. They practice body scarification after having killed an enemy.

Mursi males are known for their fierce fighting culture. Young unmarried men use to fight with a stick called donga to prove their braveness before they can get married.

Shaved bald and wearing light clothes, the young adults confront each other with their sticks. The winner then chooses his future bride in consultation with a college of local women.

As donga fighting can lead to serious injuries, it is nowadays prohibited to run it in front of foreign visitors.

On the following morning, we leave the Mursi village. Their chief accompanies us on a leg of the journey as he wishes to visit one of his relatives in another Mursi village.

‘A nice guy’, concludes my guide. Happy to have met such a nice guy who introduced me to his Mursi community.

Cheers,