This is the first of four posts on Sainte-Marie island, structured along the guiding rod of piracy in 17th to 19th century and its imprint on today’s life in the island.

As it sets the scene and deals essentially with history, the present post consists in many words and few pictures. The next elements of the series will be more visual. The historical part of this post summarises the variety of documentary and oral sources consulted. In contrast, the field search part is fictional. It represents a creative essay drawing upon my travels throughout the island and reshaped by my imagination. All pictures are mine and were crafted in Sainte-Marie recently.

Located east of Madagascar’s main island and west from La Réunion, Sainte-Marie was called first Ibrahim’s island. Early 16th century, Portuguese sailors found refuge on the island after having suffered a shipwreck. As the incident took place on the day of the Assumption according to the Roman catholic religious calendar, they renamed the place Santa-Maria. Sainte-Marie island is called Nosy Bohara in Malagasy language.

Sainte-Marie served as rear base and monitoring point for French, English, Portuguese and Dutch pirates operating in the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea from the 17th century to the early 19th century. The Pirates bay located near present-day Diego Suarez in the north of Madagascar served a similar purpose.

Worth recalling here that pirates (French synonyms: forbans, flibustiers) refer to seamen pillaging ships for their own account. In turn, corsairs were private seamen officially commissioned by western powers to seize ships of other nations or to neutralize pirates ships. In fact, a number of corsairs turned pirates over time.

Piracy based in Madagascar existed in the early 17th century and developed in the last decades of the century. Many pirates who settled in Madagascar in the late 17th century operated first in the Caribbean. At that time, western powers intensified their repression of piracy in the New World. Pirates were seen as undermining the safety of maritime trade as well as challenging the political and the religious social order in Europe through its libertarian and egalitarian ideas.

According to some sources, a handful of French pirates founded a small republic near Diego Suarez in the north of Madagascar in the 18th century – before the American and the French revolutions. Shaped by libertarian and egalitarian values, their republic was named Libertalia. Many historians question the historical evidence of the pirates’ republic. If it ever existed, Libertalia was a short-lived experiment.

In contrast, there is no historical doubt about Sainte-Marie island having harboured western pirates from the 17th century to the early 19th century. About 1,000 European pirates were based in Sainte-Marie in the 18thcentury. They gave their name to an islet in Sainte-Marie – Île aux Forbans – and to the nearby cemetery. A French official based in Sainte-Marie married with a local ruler, Queen Betsy (or Betty), during the same period, connecting Sainte-Marie island strongly with France. There are still many references to European pirates in present-day life in Sainte-Marie.

Sainte-Marie island suited well to the needs of the pirates, looking for remote but strategic locations near the main commercial routes of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Various locations were used by pirates along the oriental shore of Madagascar main island. In the vicinity of Sainte-Marie, a narrow channel near Tataingo bay provided them with an ideal environment to ambush merchant boats.

Many famous pirates stayed in Sainte-Marie for short or longer periods, such as the English Thomas Tew, Christopher Condent, Henry Avery, William Kidd, Edward England, John Taylor, as well as the French Olivier Levasseur nicknamed La Buse.

Sea piracy in the Indian Ocean was a risky but lucrative endeavour. Also known as The King of Pirates, Henry Avery teamed up with a few other pirate ships to overrun the Ganj-i-Sawai and her escort ship in 1695. The luxury dhow was transporting the daughter of the Indian Mogul Emperor Aurangzeb from Mocha in Yemen to Surat in India with colossal amounts of gold and other precious items.

After the seizure of the two Indian ships and the looting of their precious cargo, Avery proposed to his fellow pirates to transport the entire booty on his vessel to a safe location before the sharing. Instead, he disappeared and sailed to the West Indies (Antilles). In retaliation, the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb closed five key Indian ports to English trade until Henry Avery would be caught and executed. While Avery was never captured and hung, he died in an unknown location in the late 17th century, sick and miserable.

In 1721, La Buse, who operated together with John Taylor from Sainte-Marie, boldly seized the Nossa Senhora do Cabo – flagship of the Portuguese Navy anchored near Saint-Denis in Bourbon island (today’s La Réunion). On board, the vice-roy of the Portuguese Oriental Indies, his court as well as the Goa archbishop. The Portuguese officials were returning to Lisbon after years of service in India with huge amounts of precious goods. Captured by the French in Madagascar, La Buse was tried and hung in La Réunion in 1729 without disclosing the location of his treasure.

The two accounts illustrate how much growing piracy in the Indian Ocean in the 18th century put at risk the European main powers’ commercial and colonial ambitions in India. Hence their subsequent efforts to eradicate piracy in the Indian Ocean through similar means than in the Caribbean – a combination of repression and pardon.

The two stories also epitomise the pirates’ challenging and opaque wealth management: “Richesse mal acquise ne profite pas”, states a French saying. Neither Avery nor La Buse enjoyed the full financial benefits of their piracy act. Furthermore, none of their respective treasures was found in full since then.

Legend has it that some of the treasures amassed by the pirates operating in the Indian Ocean during that time period are still hidden in Sainte-Marie island or its surroundings. Based on extensive reading of relevant literature, I decided to search by myself, starting with the historical hideout of the pirates in Sainte-Marie.

Sainte-Marie’s pirates cemetery

Aboard a wooden pirogue, my local guide leads me first to the so-called pirates cemetery in the baie des Forbans. Imagine a tiny artificial islet barely emerging from the water, whose surface shrinks year after year as it was essentially built with coral material.

I feel quite emotional while visiting the well-kept luxuriant place, hosting dozens of ancient tombstones dispersed an uncertain order.

There is an estimated 1,500 sets of human remains buried there, essentially French nationals. Those individuals were mostly pirates, but also colons or officials of the French administration. Other European pirates were inhumed in other places in the bay. No local resident of Sainte-Marie was ever buried there.

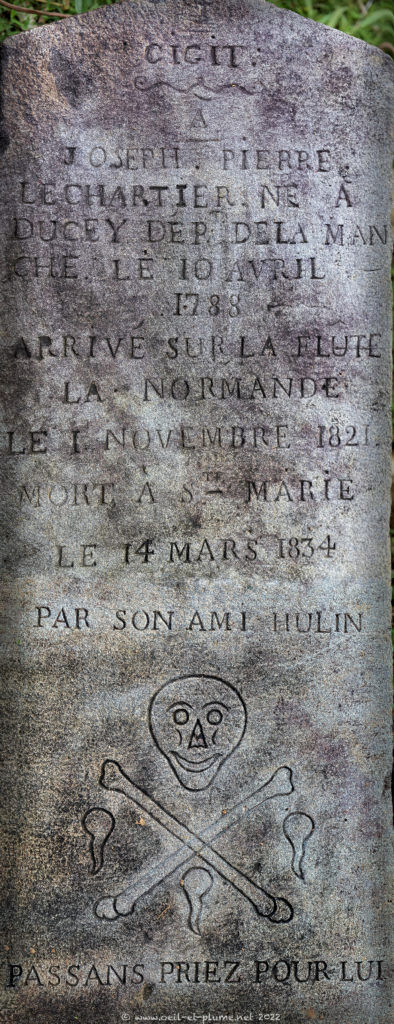

Many tombstones were flooded and flushed away by the cyclones and the soil erosion over time. Amongst the remaining stones, a few still bear identifiable inscriptions. Those relate to individuals deceased in the 19thcentury and equipped with hard stone.

The tombstones dating 17th and 18th century were made of soft coral stone which much deteriorated over time. Vandalism caused also some irreparable damages to some ancient graves, under the naïve idea that they would contain valuable items.

As piracy in the Indian Ocean was a risky endeavour, pirates’ life expectancy was very limited: According to the information displayed by the tombstones, most of them died in their thirties or early forties, with a minority reaching their fifties and beyond. This fits well with one French pirates’ mottos: “Une vie courte et joyeuse, telle sera ma devise.”

Many pirates died during their lucrative activity; they were reputed to fight to death as they would be executed anyway in case of their capture. In fact, many pirates died of natural causes – primarily malaria and other tropical diseases considering the absence of proper healthcare.

My guide tells me about the life story of a handful of deceased individuals buried in the cemetery. One of those stories touched me deeply: It is about two French pirates who befriended in the early 19th century until Joseph Pierre Le Chartier looted his friend Hulin of his booty share. Hulin identified the thief and killed his friend to avenge the robbery. Pirates used to sanction treason and robbery amongst themselves with death sentence. Hulin financed the decent burial of his former friend in the pirates cemetery. However, he engraved the following ironic words enriched with a sarcastic pirate logotype on the tombstone.

No, I did not pray for Joseph Pierre, nor for Hulin whose tombstone is unknown to me. There would be many more life stories to share below, but you and me are longing to visit the île des Forbans.

Sainte-Marie’s île des Forbans

The île des Forbans is only a few hundred meters away from the pirates cemetery. In the late 17th century, the French pirates elected the islet as their base in Sainte-Marie. The English, Portuguese and Dutch settled in various locations around the same bay. The local rulers were living nearby on today’s Ilot-Madame.

The round-shaped île aux Forbans is of very modest size but of strategic importance as it allows an close monitoring of the narrow passage between Sainte-Marie and Madagascar’s main island. The smaller ships were anchored along a pier in front of the Ocean while the larger ones were hidden behind the islet.

On the île des Forbans, the French pirates dug a shallow water well, fish tanks and other amenities. Various houses were built as well, as well as an underwater tunnel to Sainte-Marie island across the bay.

The infrastructural work has been probably carried out by slaves who were either captured from the seizure of slave ships or obtained locally. Slaves were kept on the île des Forbans which constitutes a natural prison, until they were sold. Based on a trilateral agreement between the local rulers, the French company of Oriental Indies and the French pirates, such slave trade fed the expansion of colonial agriculture such as sugar-can fields in Bourbon island.

Back from their illicit enterprises, the French pirates used to share their loot on the île des Forbans. Women were not allowed there. They are also not welcomed on the pirates’ ships, believed to bring bad luck to the seamen.

I did not find any treasure on both locations visited, except for a wealth of historical information which fuelled deep emotions. To reconstitute and imagine the life of those outlaw seamen and their social environment of the past proved to be fascinating to me and hopefully to you as well.

Herewith, we stand on the very top of Forbans island, with an awesome mangrove landscape in our back. You and me are scrutinising the horizon beyond Ilot-Madame through our maritime telescope to spot for prey ships.

More seriously, I hope that those French pirates realised that such an awesome panoramic view constitutes a treasure in itself. I doubt they did.

Cheers,