Royal fairy tale

Once upon time in a faraway land, a prince married a beautiful princess in a nation-wide joyful celebration. They lived happily with their growing family to the utmost satisfaction of their people.

Fairy tale ? It happened recently in Bhutan – a Buddhist Kingdom cradled in the Himalayan heights. On 13 October 2011, the charismatic Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck – the fifth Dragon King of the Kingdom of Bhutan – marries his 21-year old bride Jetsun Pema. Although the bride is not a princess by birth, she looks very much so.

Following a purification ceremony performed by Bhutan’s top Buddhist cleric, the royal couple is gifted a mirror, curd, grass and a conch – blessings for longevity, wisdom, purity. Jetsun becomes officially Bhutan’s Dragon Queen.

Commonly named Dasho Khesar, his royal husband eventually declares he will take only one wife, unlike his father the forth Dragon King who has married four sisters at a time. The fifth Dragon King and the Dragon Queen expect their first child, a son, early 2016.

Bhutan’s geography and history are quite peculiar. The tiny landlocked country plays for centuries on its geographic isolation to protect itself from outside influences. Sandwiched between its giant neighbours China to the north and India to the south, Bhutan long maintains an isolationism aiming at preserving its cultural heritage and political independence.

The Buddhist Kingdom joins the United Nations in 1971 only. Foreigners are allowed to visit the country only by the end of the 20th century, and only then in small numbers. Bhutan is keen to preserve its traditional culture dating back to the mid-17th century.

Bhutan is often referred as to Asia’s Switzerland. With some 38.000 sq km, the Buddhist Kingdom is slighlty smaller but far less populated : a mere 735.000 inhabitants, i.e. about ten times less than Switzerland. As a matter of fact, the parallel between both countries draws more upon their geography and climate, and to a lesser extent to their neutral international diplomacy.

Unlike Switzerland, Bhutan still evokes a unique fantasyland enshrouded with mystery. The Land of the Thunder Dragon is also known as the last Shangri-la – an imaginary, remote and secluded paradise on Earth, blessed with great beauty and peacefulness. Let’s enter now Bhutan and appreciate its unique beauty.

Medieval dzongs

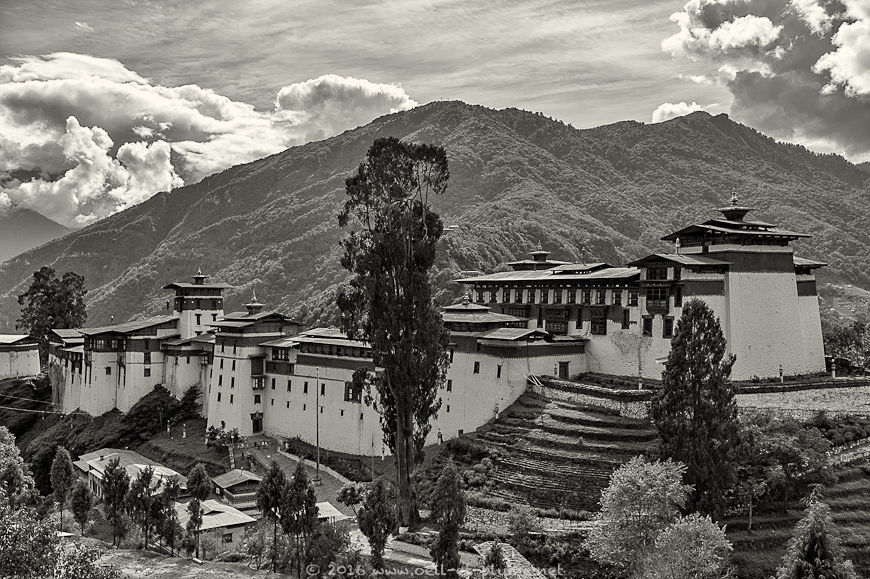

Bhutan’s dzongs are fascinating pieces of medieval architecture, serving simultaneaously as fortresses, administrative buildings and Buddhist monasteries. Not very different of some castles in Europe’s medieval times. Unlike European castles nowadays, dzongs still headquarter regional administrative authorities and host major religious communities.

Dasho Khesar is installed as governor of the Bhutan’s largest dzong located in Trongsa in the centre of the country in October 2004. In the Buthanese royal tradition, his nomination to this very position acknowledges his status of Crown Prince. Two years later, he is declared Bhutan’s fifth Dragon King.

The main royal wedding ceremony depicted above takes place in 2011 at the Punakha Dzong – second largest dzong structure in Bhutan, whose name means ‘Palace of Bliss’.

I visit both dzongs, for the utmost excitement of my visual sense. These are unforgettable moments.

Trongsa dzong is historically the seat of the Wangchuck dynasty of governors. Its strategic location allows the governors to rule over much of eastern and central Bhutan until the 19th century. Eventually, the dynasty extends its control over the whole Kingdom of Bhutan.

Trongsa dzong is a venerable structure, bearing the marks of history. The complex consists in a maze of courtyards, passageways and corridors, hosting no less than 25 temples. During the summer, the monastic community often relocates further east in the Bumthang Valley.

Punakha dzong was renovated for the 2011 royal wedding ceremony. Its somptuous and neat architecture well suits a royal fairy tale. Moreover, the main prayer’s room displays magnificent wall paintings depicting Gautama Buddha’s life course.

In the administrative part of the complex, a group of civil servants train to bow in front of high-level officials. According to the Bhutanese etiquette, bowing varies according to the social status of the official faced. High dignitaries or ministers are granted a mid-knee bowing, while His Majesty is honoured by a bowing down to the floor.

This is a well-deserved respect indeed. One of the most important responsibilites of the Dragon King involves kidu – a tradition based on the rule of a Dharma King whose sacred duty is to care for his people. In other words, Bhuddism lays at the very core of Bhutanese governance.

More Bhutanese fairy tales

Once upon time in a faraway land, an enlightened king proclaimed that happiness and well-being (Gross National Happiness, GNH) matter more than wealth accumulation and productivity (Gross National Product) in his small Himalayan kingdom cradled in the Himalayan heights.

Through the GNH concept, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, Bhutan’s forth Dragon King, positions sound political and socio-economic development at the core of public policies, in close interconnectedness with Buddhist values and precepts.

Once upon time in a faraway land, an enlightened king stated that absolute power in an unelected monarchy is not in the best interest of his Buddhist kingdom cradled in the Himalayan heights.

In addition to the GNH, Bhutan’s fourth Dragon King initiates the drafting of the country’s first Constitution, creates a National Assembly and sets to 2008 the country’s first democratic elections of the executive and legislative national authorities.

Having defined the direction and the pace of Bhutan’s transition from a medieval autocratic society to a constitutional monarchy, he abdicates voluntarily his political responsibilities for his elder son in 2005. He is then only 50 years old.

Good governance and sustainable development

To me, Bhutan’s fourth Dragon King acted as a remarkable leader in many ways. I wish to remember more examples of such rulers.

GNH may look like a populist electoral slogan or an empty lure for Bobo tourists. In fact, the concept has a larger analytical reach than the usual macro economic indicators. It considers material well-being but also other key societal determinants such as community, culture, governance, knowledge and wisdom, health, spirituality and psychological welfare, time and environmental management.

GNH’s four pillars are : 1/ economic growth and development, 2/ preservation and sustainable use of the environment, 3/ good governance, and 4/ preservation and promotion of cultural heritage. In this perspective, democracy represents then less a goal in itself than a path to good governance.

Soon after his investiture in 2006, the fifth Dragon King pursues the audacious and innovative path set by his father. The Oxford-educated Bhutanese leader ushers democratic reforms that establish a constitutional monarchy and a legislature in 2008.

Dasho Khesar, reputed as a down-to-earth and accessible ruler, travels extensively the country to discuss the draft Constitution and to stimulate democratic processes. He remains today very much tuned with his people, stressing the need for Bhutanese youth to strive for greater standards in education, as well as in the private economy and public sector.

In that respect, Bhutan follows a well-established path. There is no golden and rushed way to societal development, but a cautious, long and possibly bumpy one.

Bhutan has made of GNH not only a master policy, but also a tool of international diplomacy. The tiny Buddhist country initiated the 2011 United Nations Resolution inviting Member States to measure their happiness to improve public policies. Since then, three World Happiness Reports have been published.

Bhutan leading a process of rethinking global development ? This would constitute another fairy tale.

Cheers,

Nota Bene

The picture of His Majesties the King and the Queen of Bhutan was retrieved from open online source. Credit: Kevin Frayer / Associated Press