“Am I entitled to board the flight even if I did not bring any large flat-screen television ?’” The Thai female ground staff member preparing my air transportation from Bangkok to Thimphu in Bhutan does not resist a laugh to my joke.

All around, Bhutanese passengers are busy checking-in brand new television sets to import them home. Upon arrival in Thimphu international airport, I count 15 well-packaged monitors loaded on the luggage belt. Will 15 Bhutanese families soon be made happier ?

Television was introduced in Bhutan only in 1999, followed by the Internet. With 60% of the population under 25, Bhutan is dipping its toe into the outside world. Technology also fuels the attractiveness and the demographic growth of towns – the Bhutan way and scale indeed. Counting 100,000 residents, Thimphu is proud to remain the world’s only capital city with no traffic lights.

Rural life and development

More than 70% of Bhutan’s population still live off the land, even though only 10% of the land is cultivatable. Agriculture, livestock and forestry constitue still the economic mainstays with most of the rural population living in the fertile river valleys.

The old farmer met in a remote area of Bhumthang District carries out seasonal farming in the Bhutanese traditional way. The two bullocks drag the plough at their pace. You better be patient with them. The elder farmer and his son are working with two pairs of bullocks and two ploughing tools on the same plot since four days. They will finish today before moving to another field.

My visit to many villages across Bhutan provide further insights on the rural life. It looks idyllic at the first glance, but implies indeed hard and sustained work.

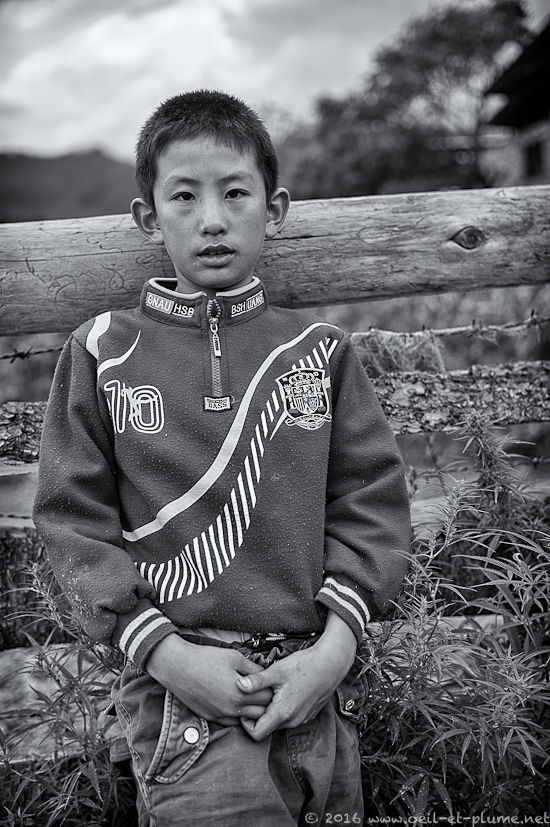

The rural youth, particularly in the less developed eastern part of the country, is increasingly reluctant to embrace traditional agriculture as source of living and lifestyle. Instead, it often looks for job opportunities in central or western Bhutan. In order to countain rural exodus , efforts are made to reinforce the provision of basic public services and to create new economic opportunites in eastern Bhutan.

Tradition and modernity – Public policies

Bhutan nurtures a rich and unique culture, closely tied in with religion. Bhutanese authorities consider the economic modernisation as the preservation of the natural environment and the national cultural identity as essential to the future of the kingdom.

Public policies are quite forward-looking : by law, 60% of the country must remain forested. Correlatively, regulations can be also quite assertive : deforesting, hunting and the use of plastic bags are prohibited ; tobacco trading and smoking in public places are outlawed as well. Despite the television story above, imports of consumer goods are restricted in order to keep Bhutan’s burgeoning consumerism under control.

Bhutan is – very legitimately – proud of its architectural style. Here as well, governmental regulations ensure the esthetic coherence of recent constructions with traditional architecture. Much attention and efforts are paid to outside adornment.

Tradition and modernity – Social structure

Bhutan’s medieval society was structured very much along local chiefdoms and serfdoms. As part of the third Dragon King modernization efforts, serfdom and other forms of forced labour were abolished in the 1950’s. Today’s rural Bhutan is still reminiscent of the medieval legacy.

An awesome journey into the Tang Valley in Bumthang District brings me to the Ugyen Choling Palace. Until not long ago, access was only possible for pedestrians through a suspension bridge of this kind. A small arch bridge extended by a steep dirt road allow now an easier access to the uphill rural settlement.

Longchen Rabjam, a Tibetan Buddhist master of Buddhism selects the location to meditate in a cave in the 14th century. The auspicious place becomes later a religious centre under the spiritual leadership of the Tibetan saint Dorji Lingpa who settles there.

Alongside the religious dimension of the settlement, the Ugyen community in medieval times is structured around a local feudal landlord, whose heirs are still living there. Their manor house is built in the 17th century by a descendant of Buddhist saint Dorje Lingpa.

The abolition of serfdom associated to land reform sets a economic blow to the former ruling family in the second part of the 20th century. The latter transforms their manor into a remembrance house which can be visited.

Ugyen residents relied traditionally on local farming but also on regional trade for their living. They used to send mule caravans to purchase rice and other supplies downhill in northern India. Their commercial caravan headed then north up to Tibet to exchange their supplies against the precious salt produced in the Himalayan heights. Such regional trade is obsolete nowadays indeed.

The manor house caretaker’s sister, a writer, published various books on Bhutan’s traditions including on folk tales about the yeti. She is married with a Swiss national. I wish I would have spent a night night there, but time is money in Bhutan as well.

Bhutan’s society is evolving. Traditionnal arranged marriages with no engagement period are no longer common. Couples start often with an engagement period and marry after the female partner gets pregnant. Traditionally, an unmarried pregnant women would be shameful for the family. As divorce is legal and socially accepted, recomposed families are frequent in Bhutan.

Polygamy and polyandry are not uncommon in Bhutan, mostly amongst the nomadic tribes in rural areas. In urban settings, a love relationship is generally tolerated by the other partner as long as basic caretaking duties of the marriage are fulfilled.

Growing happiness?

I don’t resist exploring the fascinating relationship between economic development and happiness in Bhutan. Across cultures, wealth is usually considered as a key element of when not the key to, happiness. How is it in Bhutan ?

Bhutan is one of the lower middle income countries as defined by the World Bank. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) expressed in real terms expanded yearly by 4.0% to 12.6% during the 2003-2014 period, with a low in 2003 and a high on 2007. GDP per capita amounted to USD 2,852 – roughly twice as much as in 2003. Unemployment rate was slightly above 3.0% in recent years.

We can conclude on a robust and sustained growth of Bhutan’s economy, alongside its cautious opening to the world. So what about happiness ?

According to the 2015 national survey on Gross National Happiness (GNH), Bhutanese people were overall happier in 2015 than they were in 2010. Improved living standards and public services, better health and access to culture were amongst the key vectors of increased GNH.

Not all Buthanese people were equally happier in 2015, tough : 1/ men were happier than women ; 2/ farmers were less happy than other professionals ; 3/ people in urban dwellers were happier than rural residents ; 4/ educated people were happier than those not.

The 2015 survey in Thimpu illustrates a rather classical socio-economic transformation. Local residents are wealthier on average, but also subject to widening income gaps. Poverty affects those who remain jobless. Thimphu ranks low in GNH because of the dilution of culture, community vitality, psychological well-being, spirituality and environment.

The relation between development and happiness is well captured by the GNH concept. GNH does not constitute per se a promise of happiness, as happiness constitutes an individual goal. GNH expresses rather a governmental responsibility to create the enabling environment for citizens to seek happiness.

Not all people are equal in their search indeed, given the manyfold definitions of happiness. Wealth does not make one necessarily happier, but it usually helps – until individual choices and preferences take over.

On a more down-to-earth level, I found Bhutanese people humour-full and fun-loving. Does this constitute a compelling evidence of happiness ? I believe so.

On my side, I felt happy throughout my stay in Bhutan. However, I would have been maybe very happy with a large flat-screen television set. Lesson learnt : the essential device is now part of my globetrotting survival kit.

Cheers,